Always! DS is the backbone of OSGi. Whenever you write code in OSGi you write them as DS components.

Not sure what we were smoking when designing the original OSGi specification, or maybe it was just youthful exuberance, but OSGi did not really become useful for the rest of us until we had Declarative Services (DS) with their annotations. Though some old hardliners still seem to resist it (see Real Men Don’t Use DS), it is obvious that if you use OSGi and not use DS you’re either extremely deep down in middleware or you’re just plain wrong.

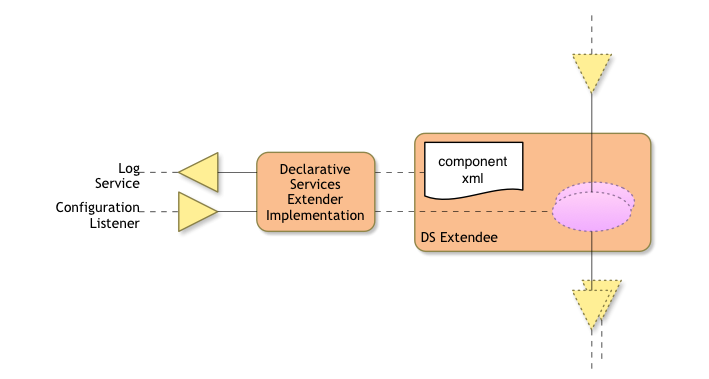

DS (or also called the Service Component Runtime SCR) is an extender that creates components from your bundle. Each component is defined in a, shudder, XML resource. In the bad old days you had to write this XML but fortunately there are now some annotations that allows bnd to write the XML on the fly. This XML file defines your dependencies, properties, and registered services. When the time comes, DS will instantiate the class, inject the dependencies, activate it, and register the services.

At first, there are many similarities with injection framework. However, this is comparing a flat space with a 3D space since DS handles dynamic dependencies. Though for many a developer the dynamics in OSGi are off putting, the advent of distributed systems makes it more and more clear that the world is dynamic and trying to hide these dynamics for the developer is a really bad idea. Over and over nature proves us trying to give the impression of a perfect world only makes us fall deeper and harder when the perfection cracks, which inevitably occurs. The beauty of DS is that it allows us to live in a dynamic world with very little effort. If you’re a skeptic, realize that those lustrous points had no clue what that Square was talking about. So bear with us, and one day you might become a beautiful Sphere!

Adding a @Component annotation to a public class will turn it into a component. Since the effects are rather pointless, let’s add a constructor so we can at least see something happening. Make sure you got the right Component annotation since, like names of children, some annotation names are clearly more popular than others.

package osgi.enroute.examples.component.examples;

import org.osgi.service.component.annotations.Component;

@Component

public class InfinitelySmallPoint {}

Obviously, this component will not win the Turing price since it does not do anything and is more or less a waste of bits, sacrificed in the goal to elucidate you. Adding a constructor and printing out a message in the constructor will allow you to verify that it actually does get constructed.

The fun part of OSGi are the services, so how can we register a service? Let’s implement an Event Handler service. Such a handler receives events from the Event Admin service. There are always events emitted by the OSGi framework so that allows us to see something. Registering a service is as simple as implementing its interface.

@Component

public class EventHandlerImpl implements EventHandler {

@Override

public void handleEvent(Event event) {

System.out.println("Event: " + event.getTopic());

}

}

Though it is not rocket science to create events (just start/stop some components and/or bundles) it would be nice for our fundamental research in OSGi components to have a steady stream. To create such a stream, we need to create Event Admin events every second. Hmm, this requires us to get access to the Event Admin service (the honest broker between the event senders and receivers) and it would be nice to have a

Initializing in a constructor is awkward and ill advised, initialization should therefore be done in a method annotated with the @Activate annotation.

@Component

public class SmallPoint {

@Activate

void activate() {

System.out.println("Hello Lustrous Point!");

}

}

We definitely improved on the usability scale but only a statistician could get excited about it. Fortunately, there is an easy way to do something useful (ok, that is stretching it still) with a component. If we give the component a few properties

Let’s start simple with single dimensional line land: dependency injection as we all know and love from Spring. Let’s inject an OSGi Log Service and allow the defaults do their work:

package osgi.enroute.examples.component.examples;

import org.osgi.service.component.annotations.Component;

import org.osgi.service.component.annotations.Reference;

import org.osgi.service.log.LogService;

@Component

public class LogExampleComponent {

@Reference

void setLog(LogService log) {

log.log(LogService.LOG_INFO, "Hello Lustrous Point!");

}

}

When you run a bundle containing this component then DS will wait until a suitable Log Service comes available. When this happens, DS will instantiate a new LogExampleComponent object and call the setLog method. Nothing spectacular. We could extend the class with an activate method and do the logging there.

@Component

public class LogExampleComponent {

private LogService log;

@Activate

void activate() {

log.log(LogService.LOG_INFO, "Hello Lustrous Point!");

}

@Reference

void setLog(LogService log) {

this.log = log;

}

}

Still, nothing to write home about. However, if you live in the real world then you know that the Log Service might also disappear. In that case, your component should no longer hold a reference. To make this happen, DS will release the object and it will be garbage collected. Of course you should clean up any mess you’ve made during the life time of your object so you can implement a deactivate method.

@Deactivate

void deactivate() {

log.log(LogService.LOG_INFO, "Goodbye Line!");

}

How hard would it be to register a service? Well, for a service we need an interface:

public interface Line {

int getDimensions();

}

And make a component:

@Component

public class LineImpl implements Line {

}

Since we now implement an interface DS makes the clever assumption that you want to register a Line µservice. Since you now register a service there is no need to immediately instantiate the component, DS will now wait until the registered µservice is used.

The OSGi Framework contains a procedural service model which provides a publish/find/bind mod- el for using services. This model is elegant and powerful, it enables the building of applications out of bundles that communicate and collaborate using these services. This specification addresses some of the complications that arise when the OSGi service model is used for larger systems and wider deployments, such as:

The service component model uses a declarative model for publishing, finding and binding to OSGi services. This model simplifies the task of authoring OSGi services by performing the work of reg- istering the service and handling service dependencies. This minimizes the amount of code a pro- grammer has to write; it also allows service components to be loaded only when they are needed. As a result, bundles need not provide a BundleActivator class to collaborate with others through the service registry. From a system perspective, the service component model means reduced startup time and potential- ly a reduction of the memory footprint. From a programmer’s point of view the service component model provides a simplified programming model. The Service Component model makes use of concepts described in 1 Automating Service Dependency Management in a Service-Oriented Component Model.